TIRED

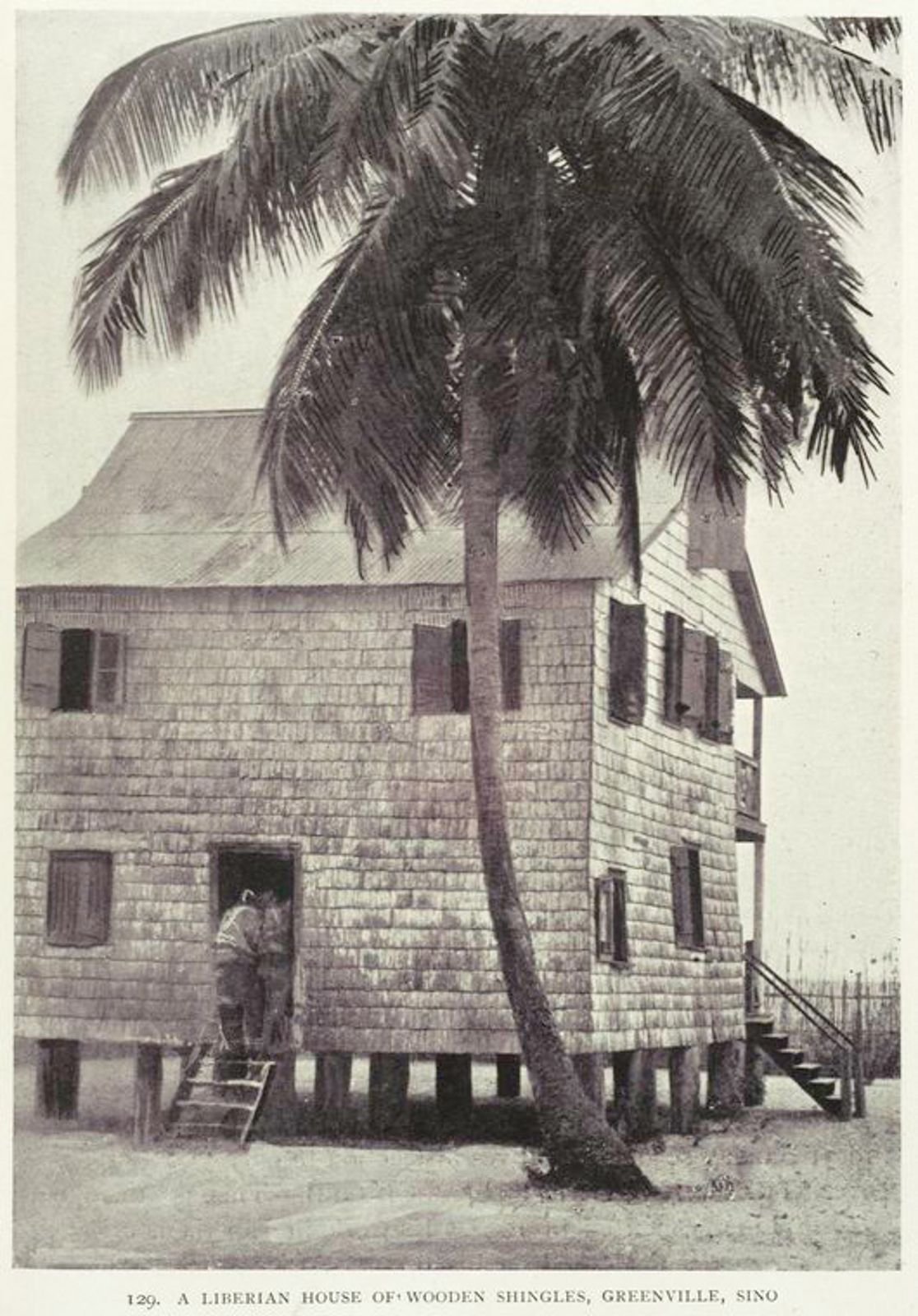

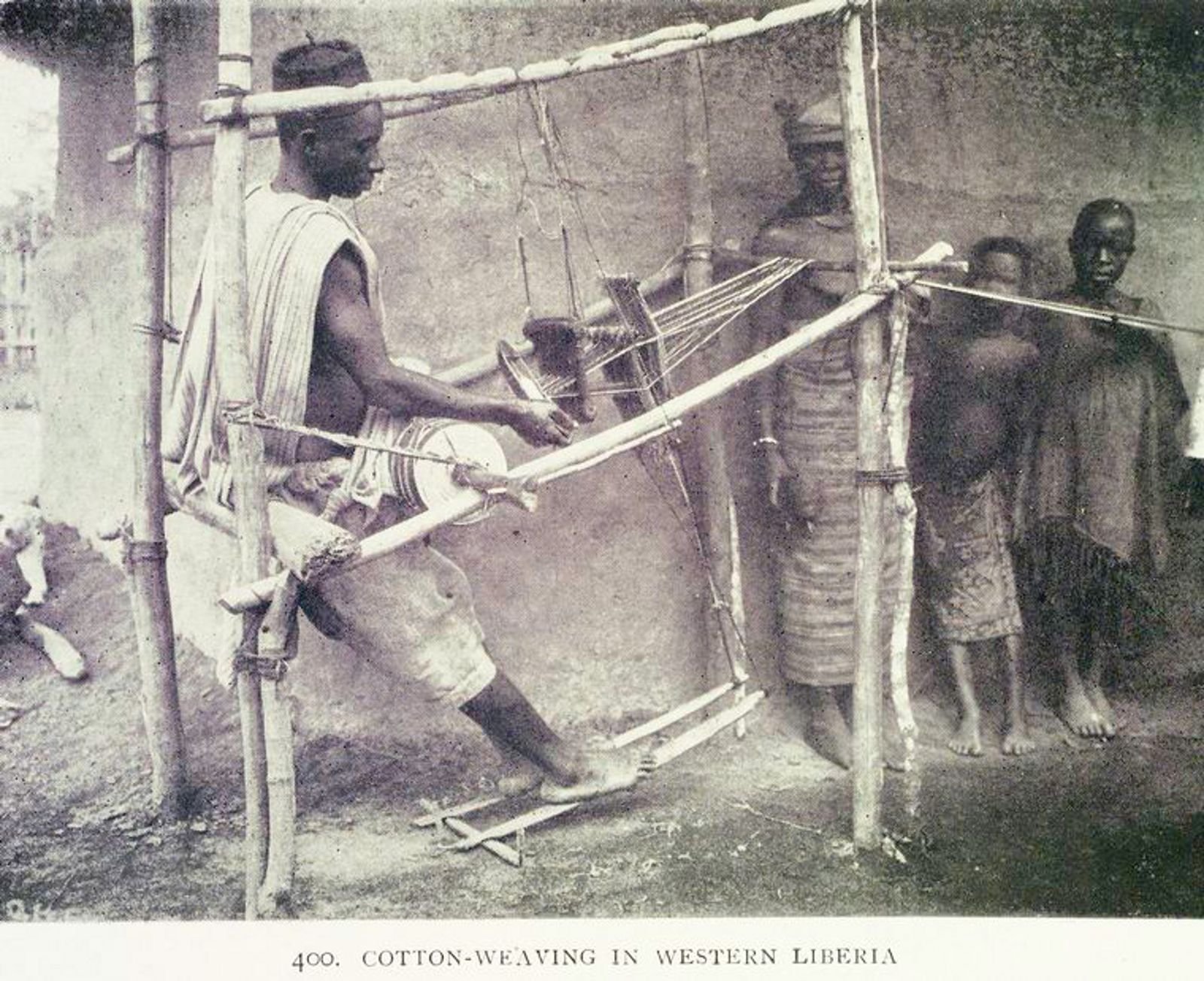

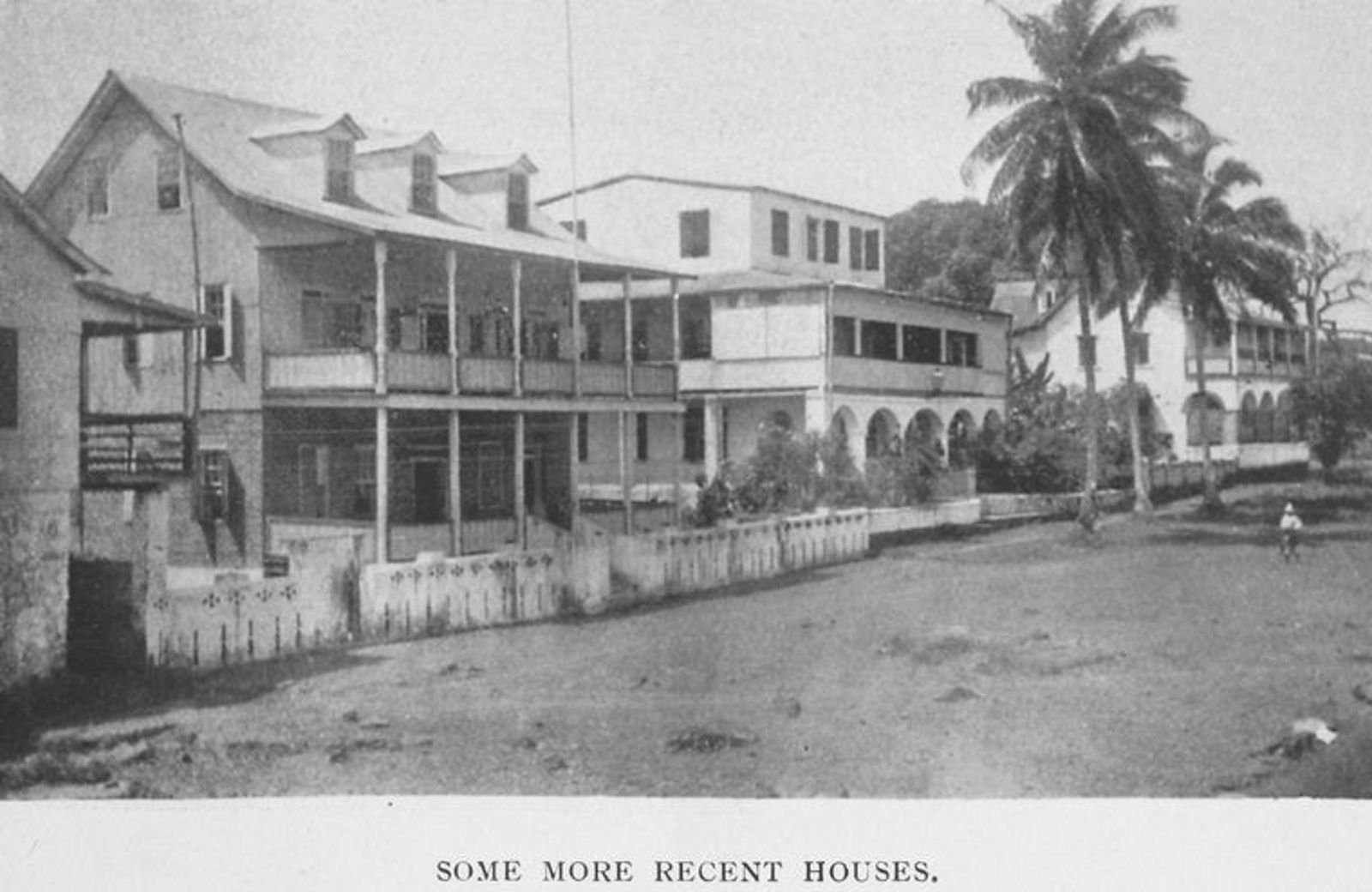

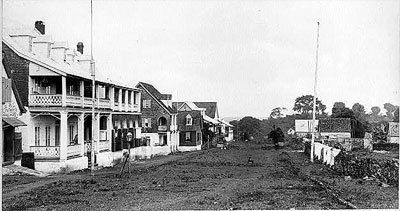

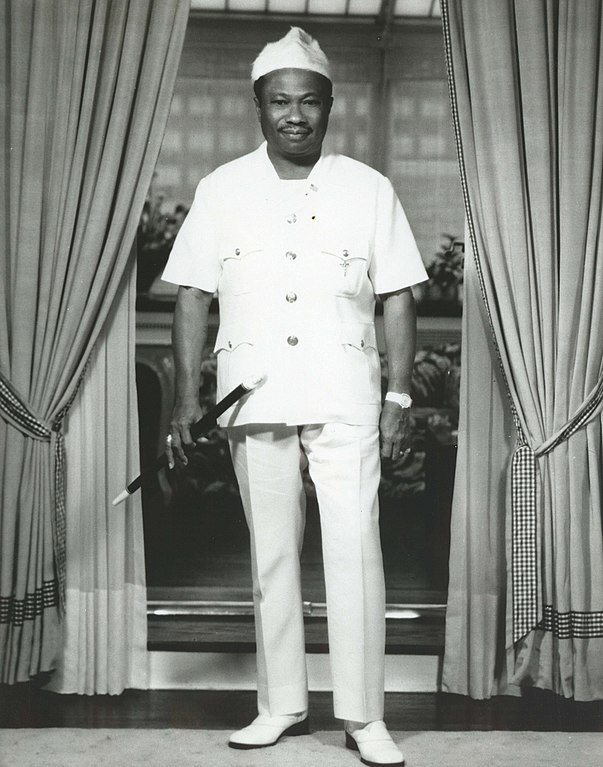

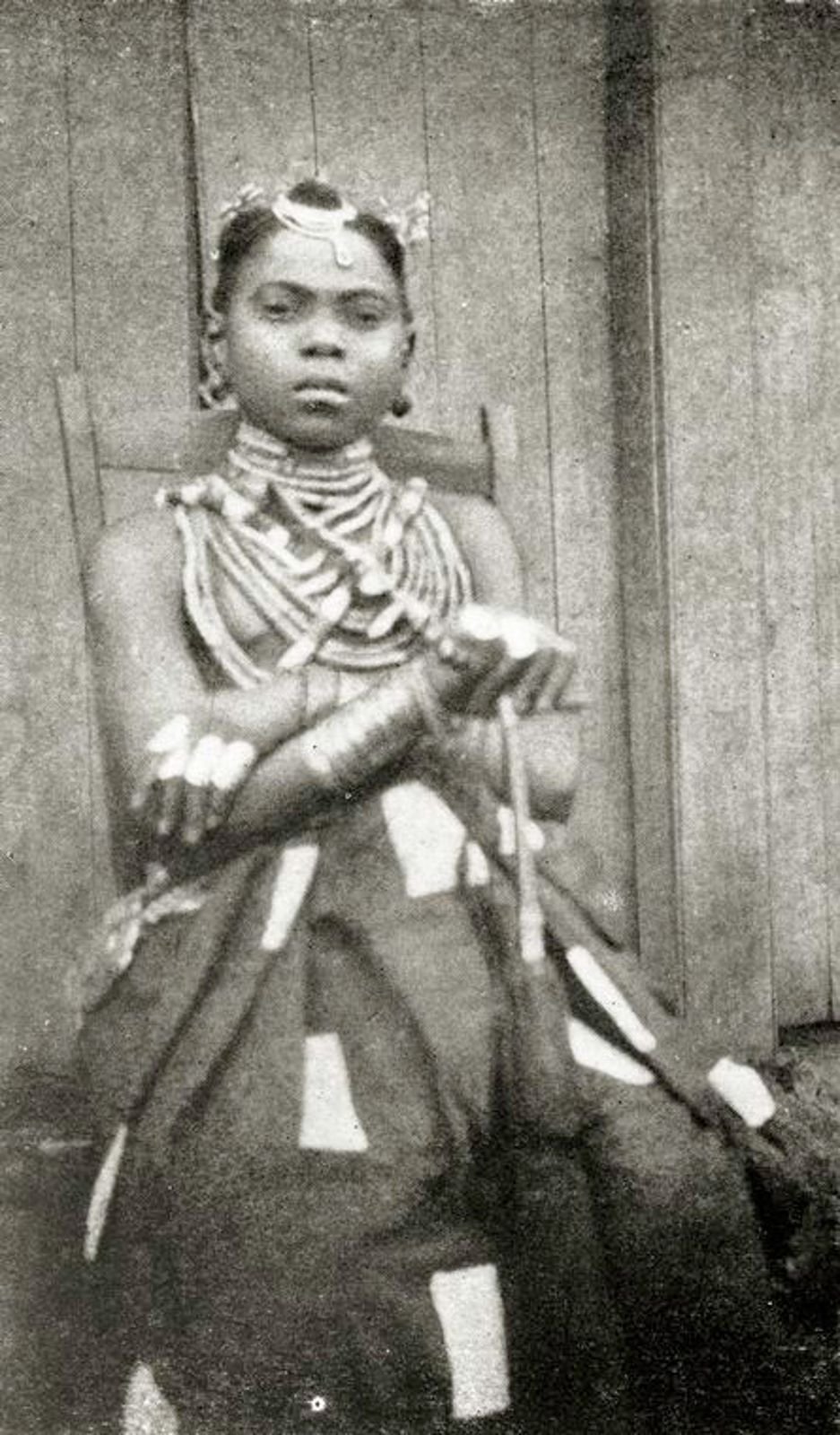

Sometimes incidents coagulate and produce ideas for a new book. Tired was born of five such events. When I was a student at Indiana University in 1980—at that time with hundreds of African grad students enrolled—I heard that one slightly older man had abruptly but permanently left for his homeland of Liberia. Why? There’d been a coup, and the new head-of-state, Samuel Doe, had recalled him to take up a government post. When I returned to the U.S. in 1988, I was working in Philadelphia and was put in touch with the late Svend Holsoe, a professor who lived nearby but taught at the University of Delaware. A historian, his main specialty was Liberia, where he’d lived while his father was working for the government. He had the largest library about Liberia in the world, and had edited the Liberian Studies Journal. He’d just written an essay for a book on old Americo-Liberian houses called Liberia: A Land and Life Remembered, and I was fascinated by it—perhaps because I had initially wanted to write my dissertation on Brazilian returnees and the Brazilian-style homes they’d built in Nigeria and Benin Republic in the late nineteenth century. When I started teaching at Cleveland State University, I received a call from Akron. A former executive of Firestone was putting his collection of Liberian art up for sale, and I introduced him to my grad student Pam McKee, who researched and created the catalogue. He had many high-quality works, some from the 1930s and before. Firestone (bought by Bridgestone) and the whole rubber town of Akron (also home to Goodyear, B. F. Goodrich, General Tire) were fascinating. Detroit wouldn’t have grown without them, and they made Akron the fastest-growing town in the nation in the 1910s. Firestone created the world’s largest rubber plantation in Liberia in 1926.

So far, these facts just lay in a lump, but other factors started to attach themselves—a course on architecture and public monuments in Philadelphia led me to a greater understanding of Black history there. A student in my African American art history class traveled to South Carolina and brought me back greeting cards by Jonathan Green, who was just beginning his career at the time as a painter of the Low Country Gullahs. I encountered a student neighbor whose family had fled Liberia for Sierra Leone in the early days of the former’s civil war. I visited Stan Hywet Hall, the Akron manor of F. A. Seiberling, founder of Goodyear. And, of course, I continued to learn about the arts and cultures of Liberia’s many ethnic groups as I read horrifying accounts of Charles Taylor’s takeover and escalations of regional war.

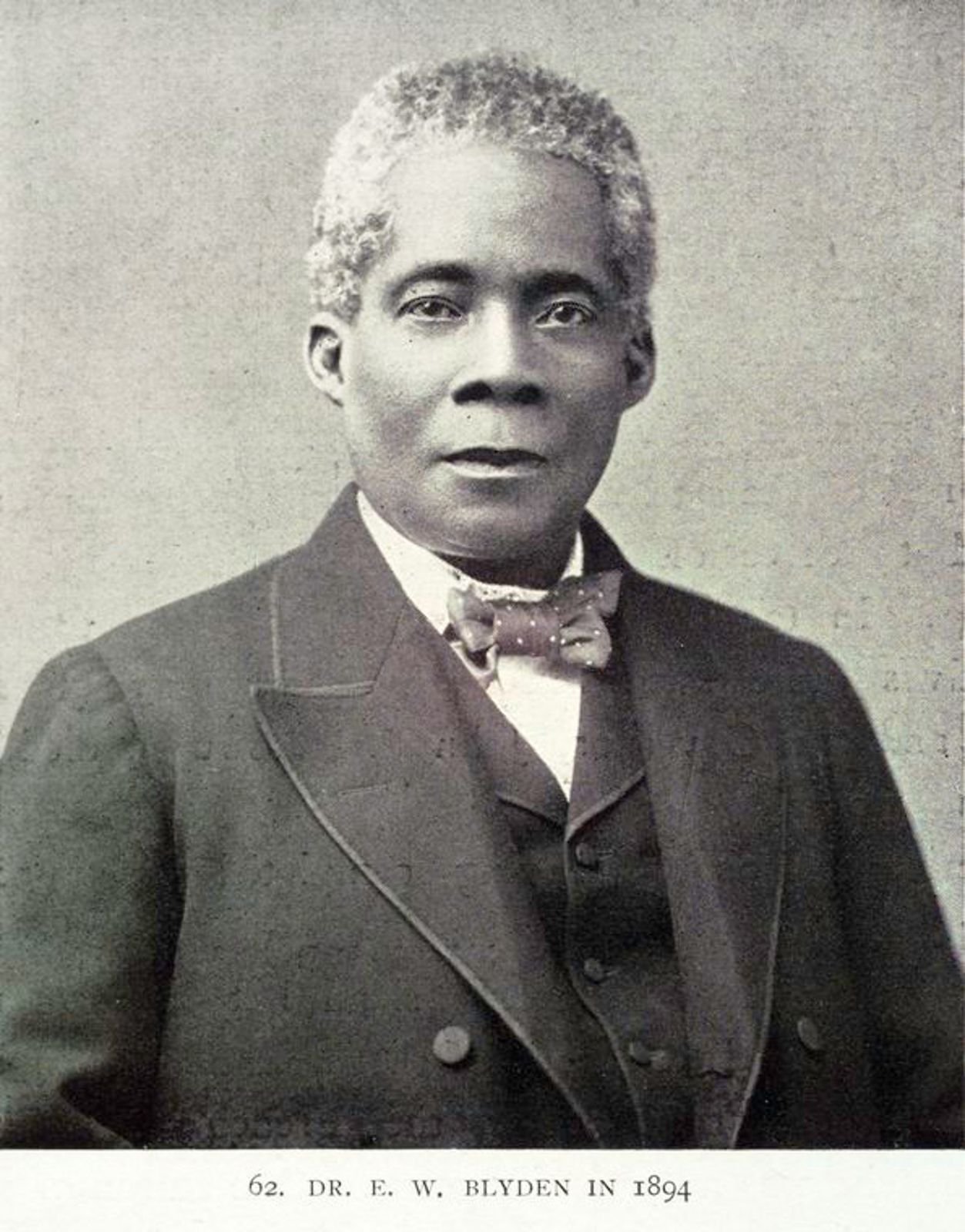

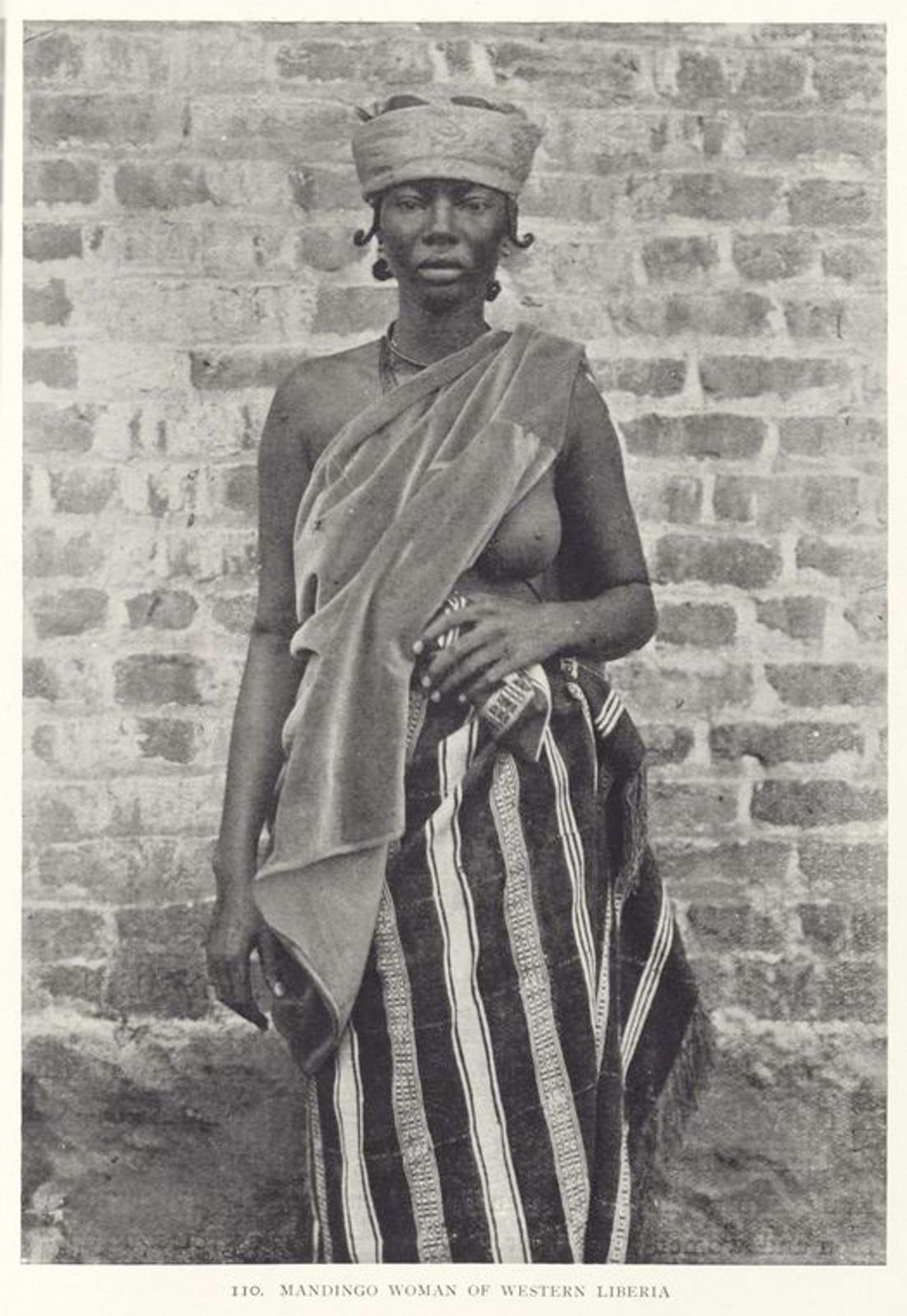

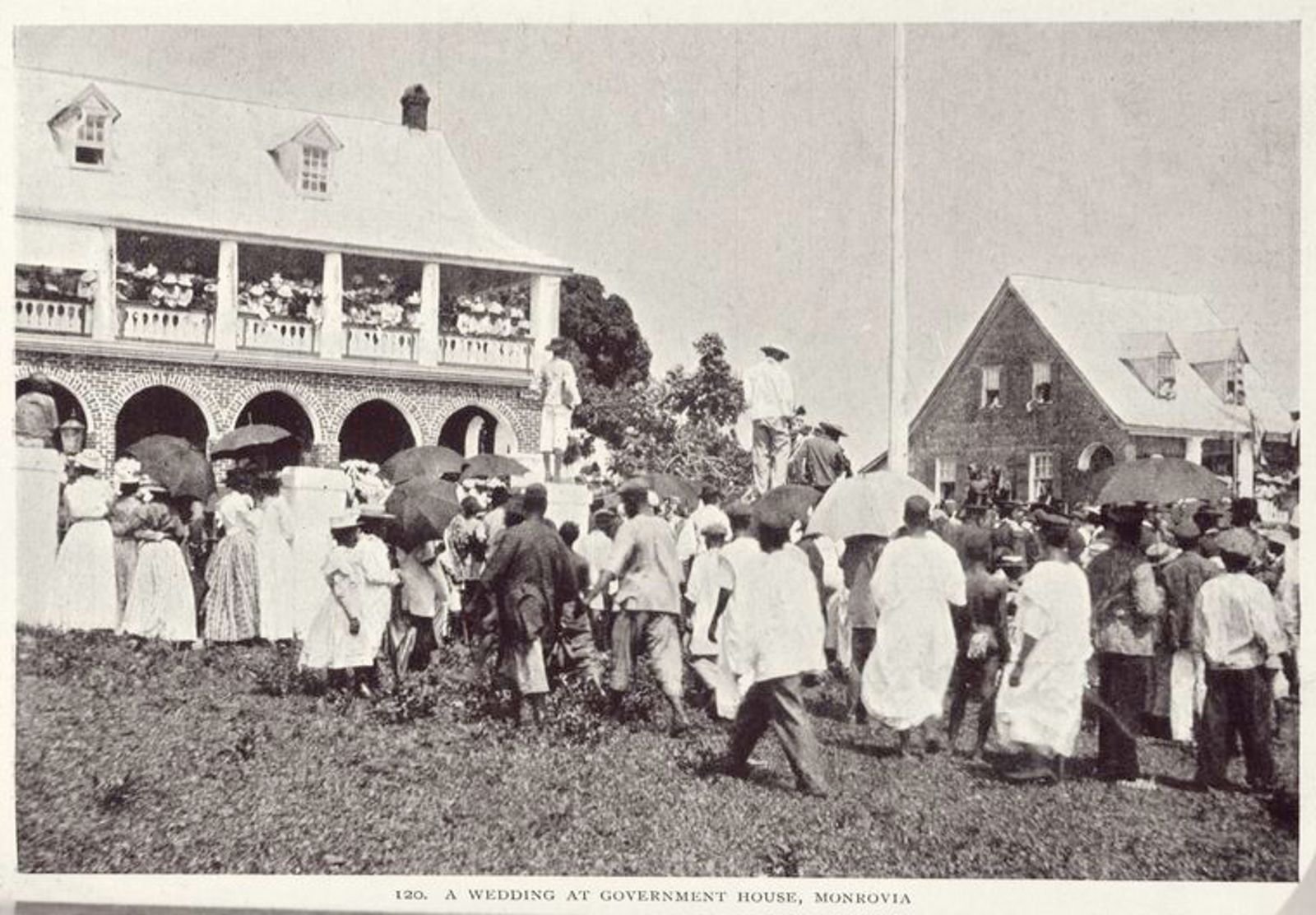

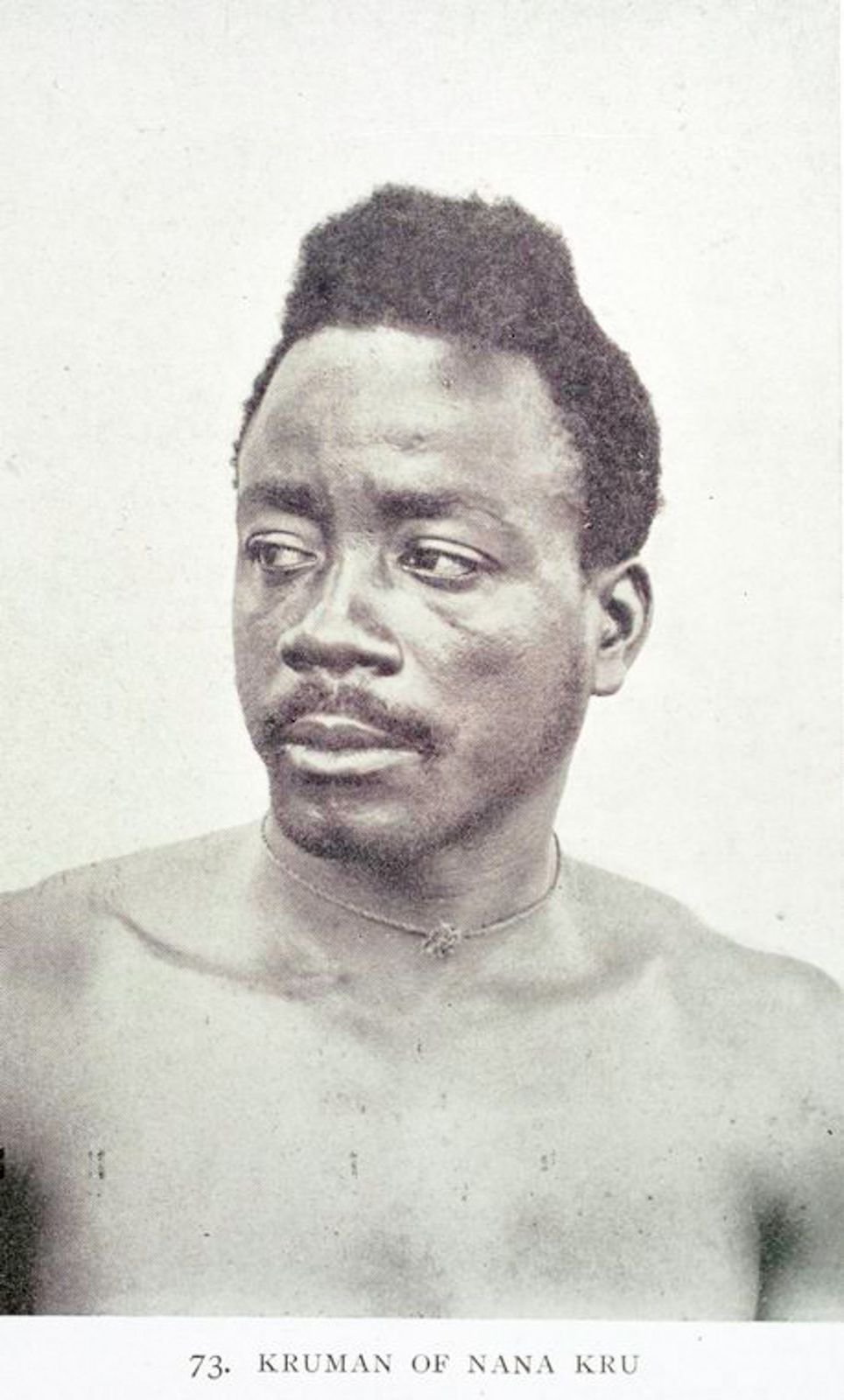

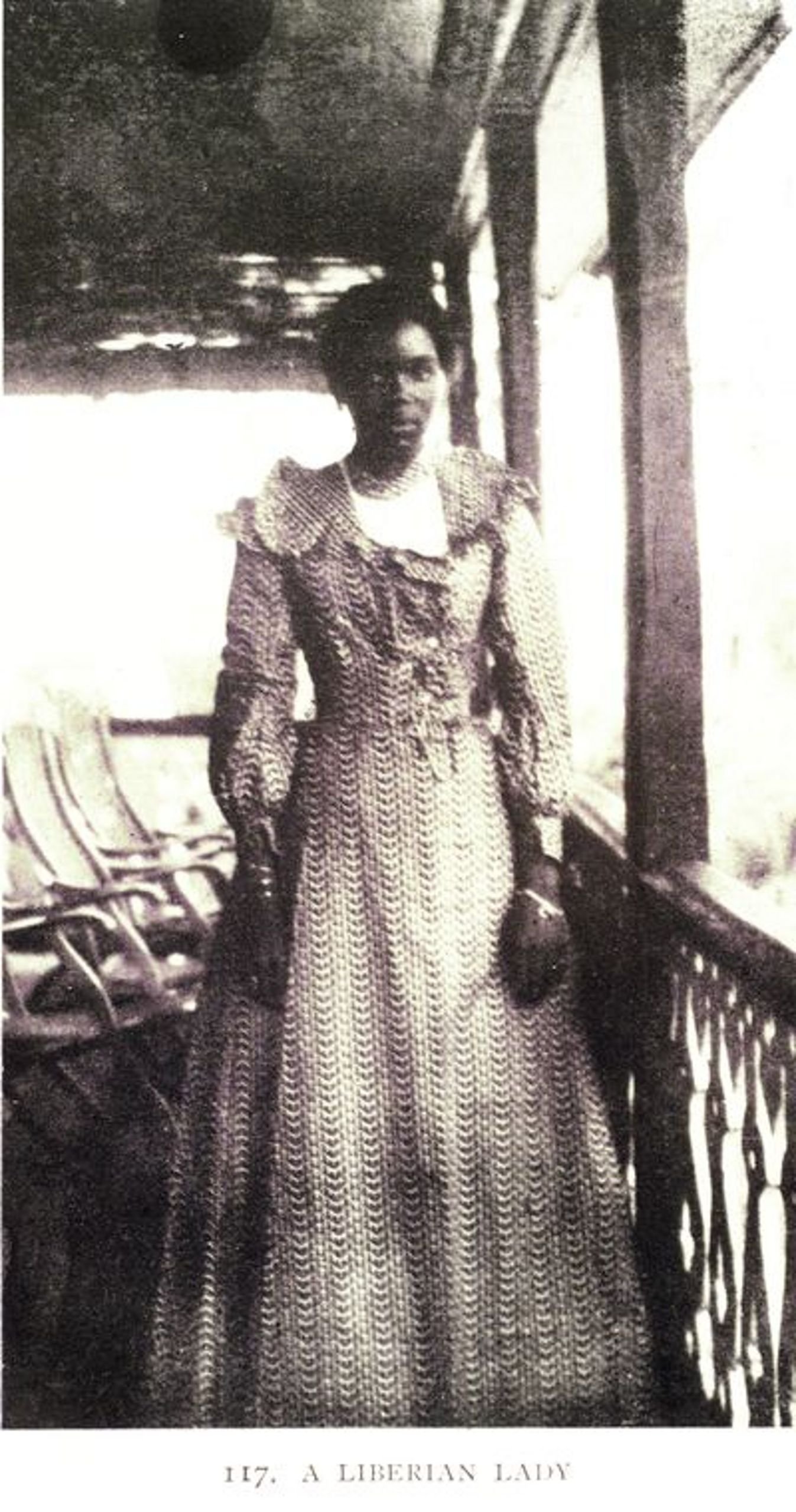

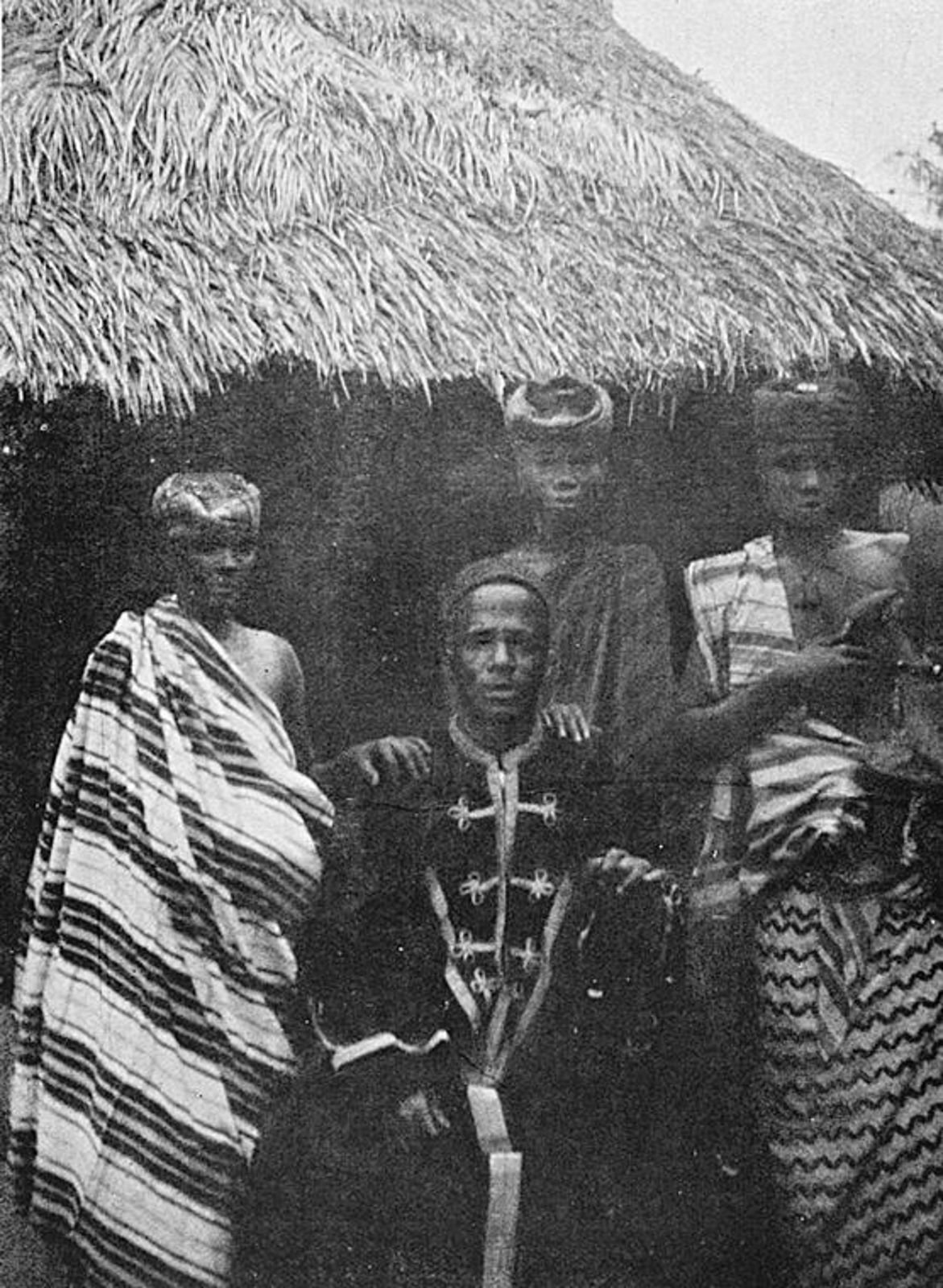

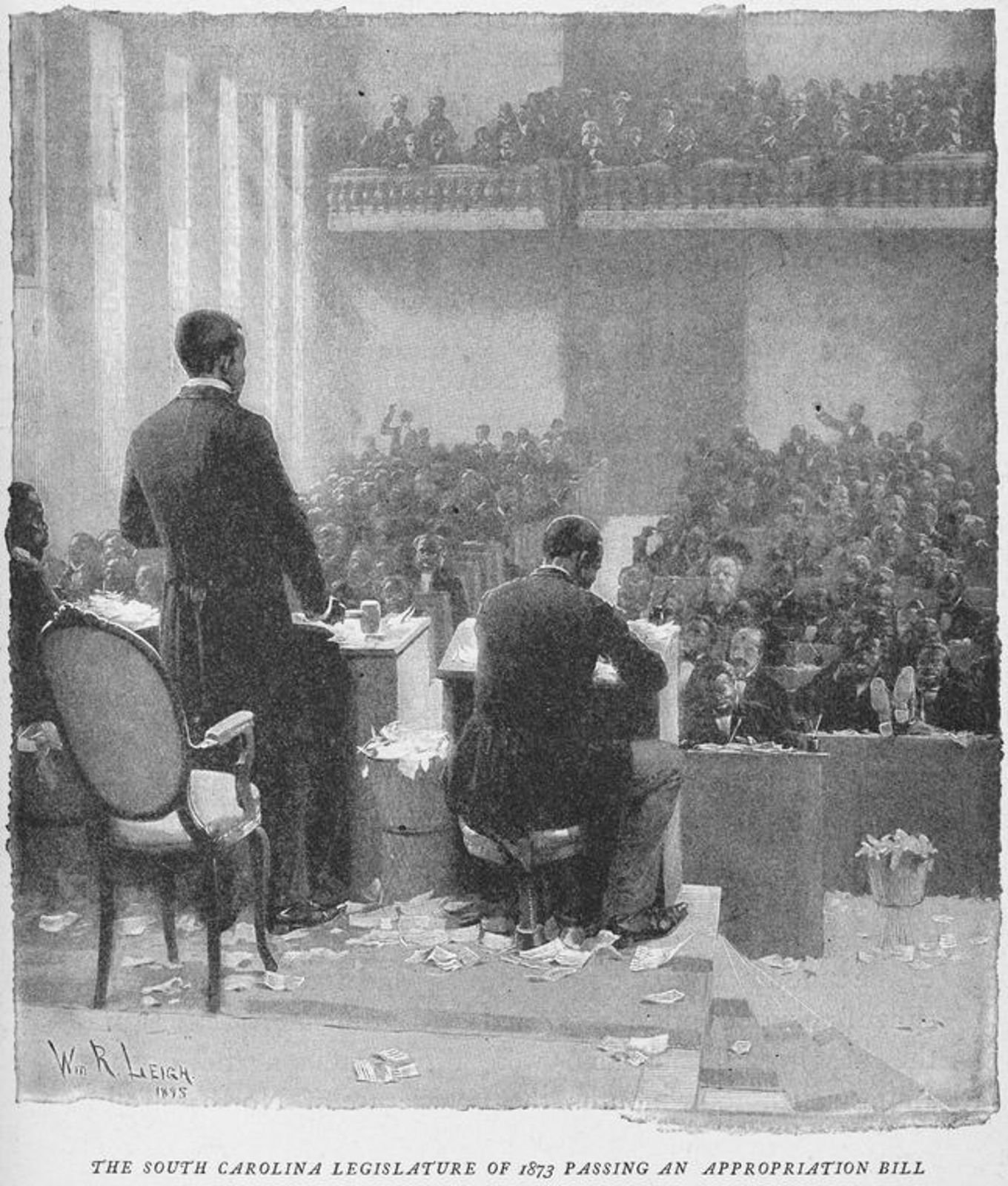

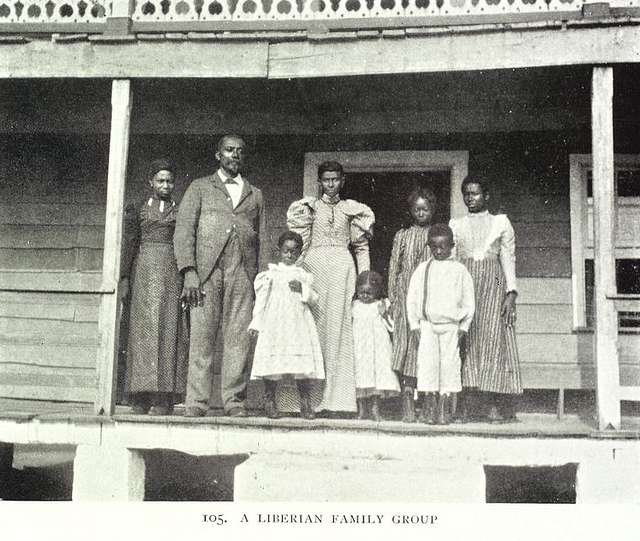

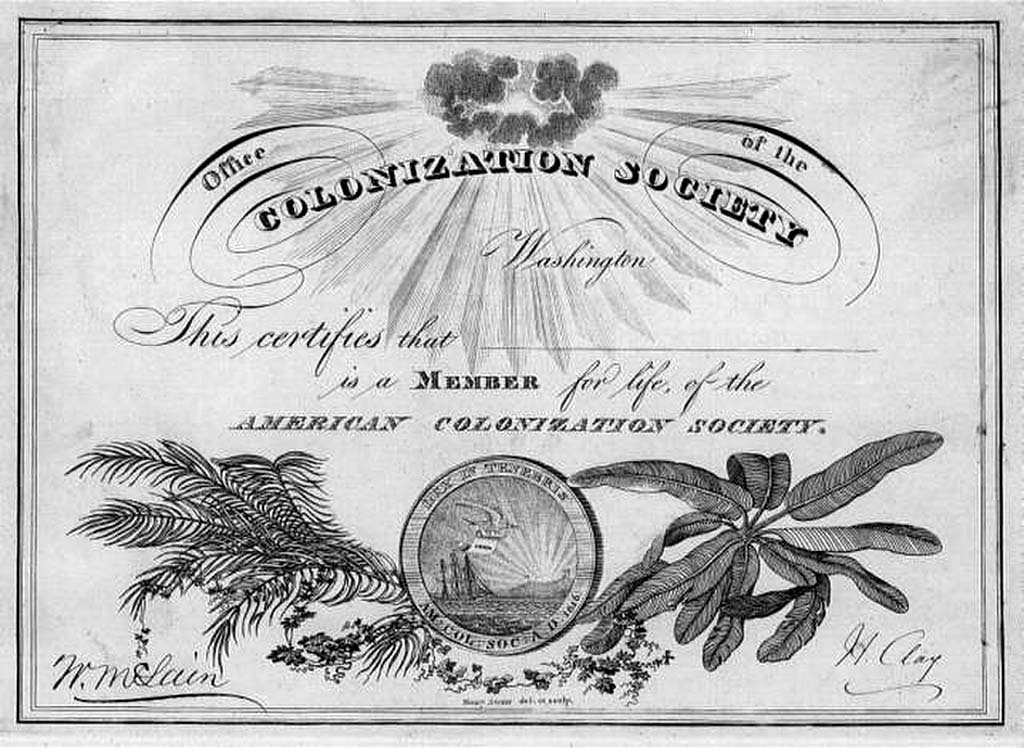

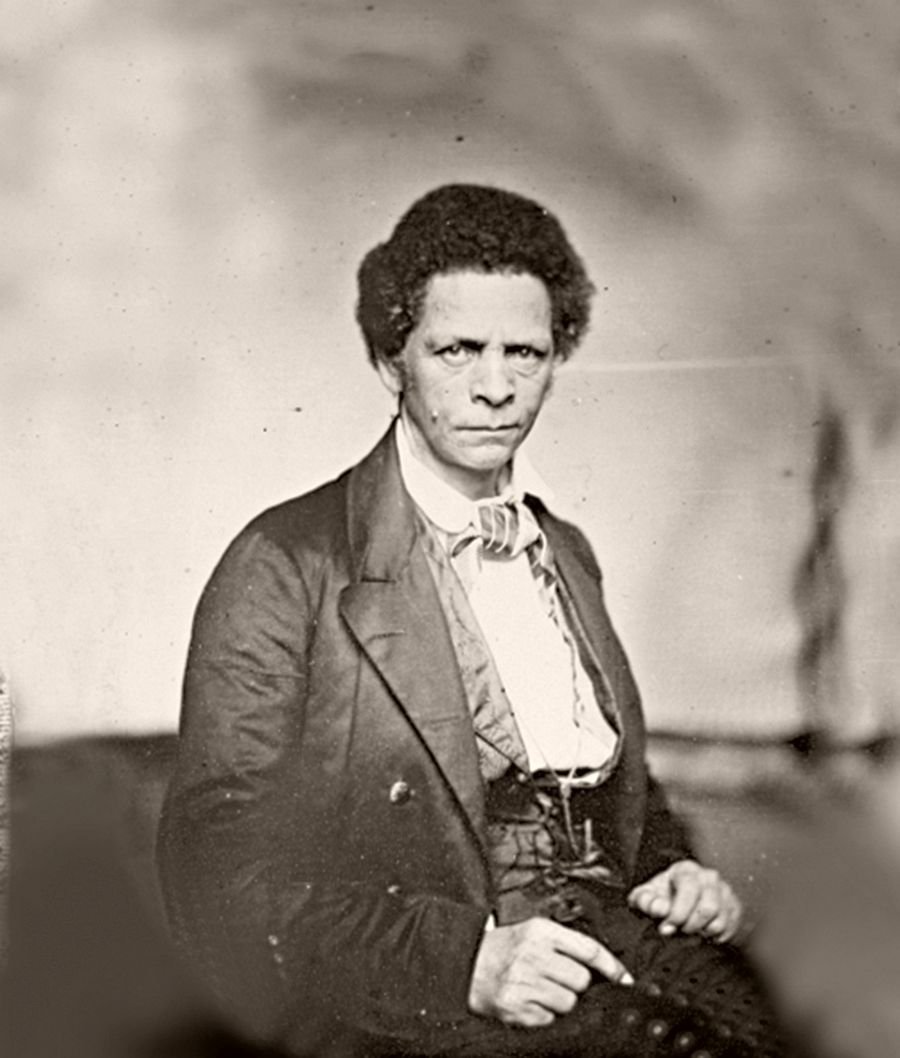

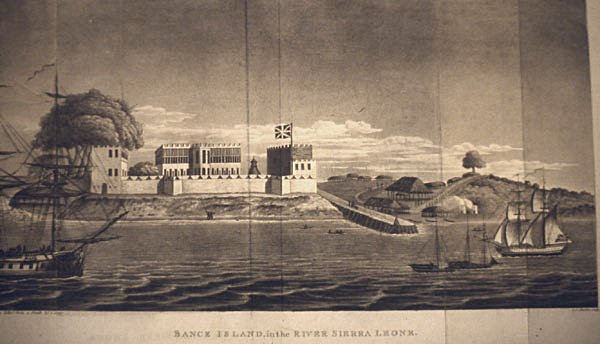

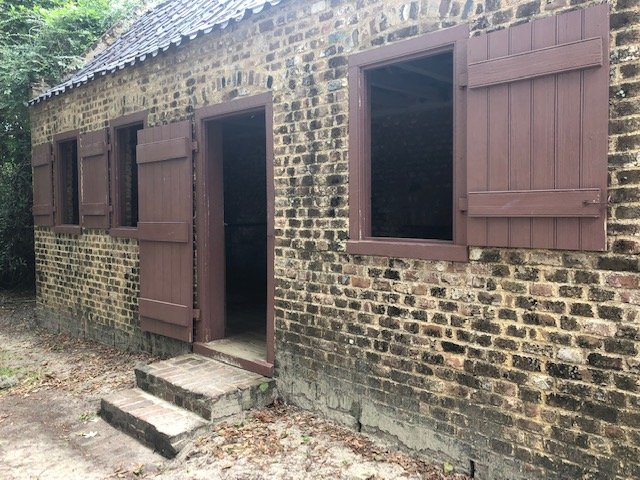

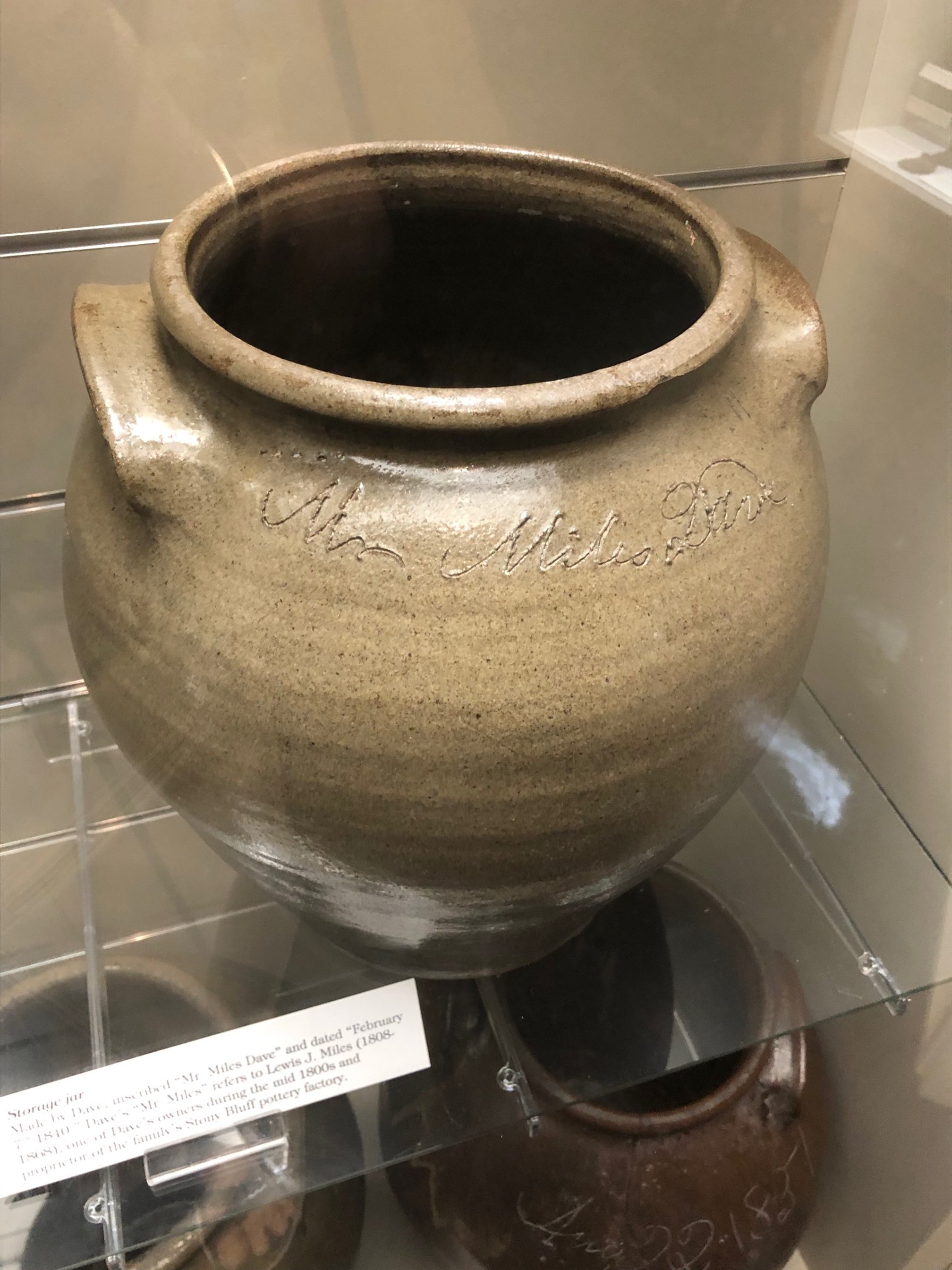

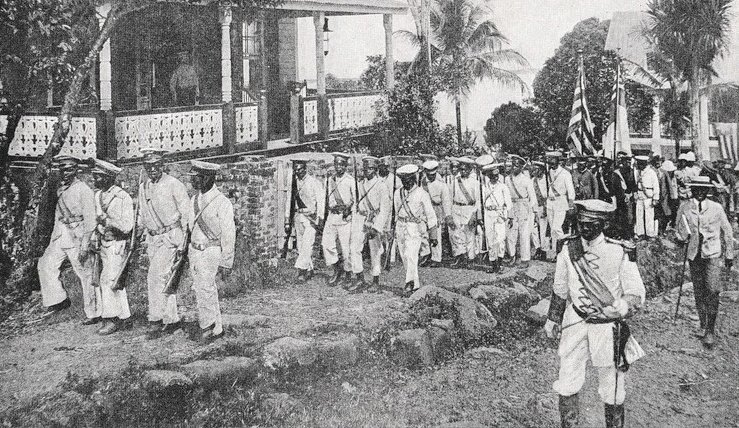

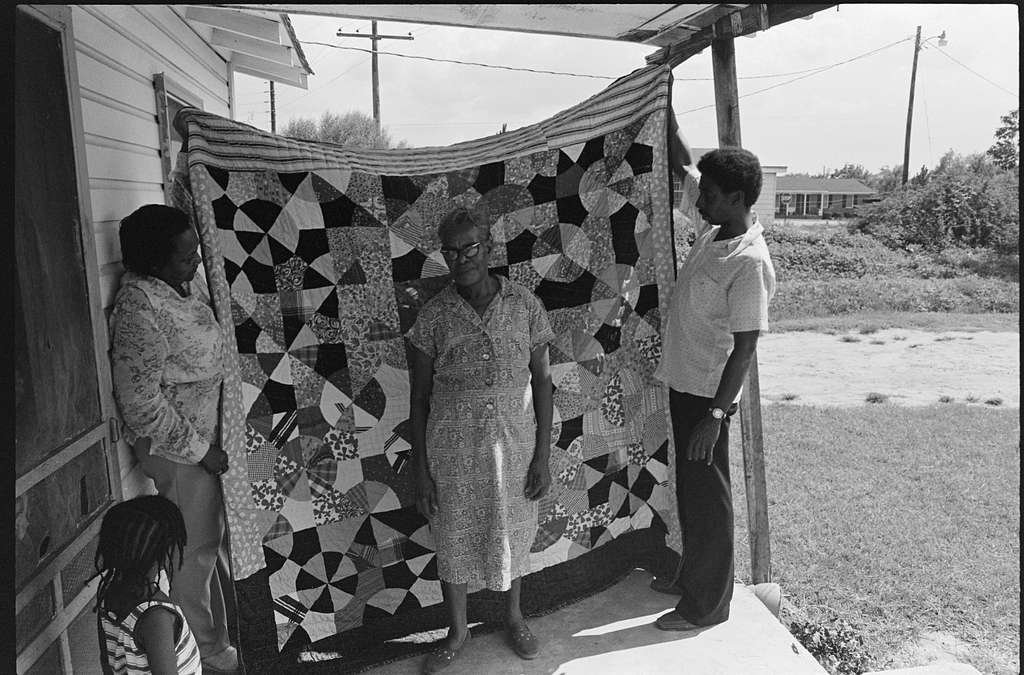

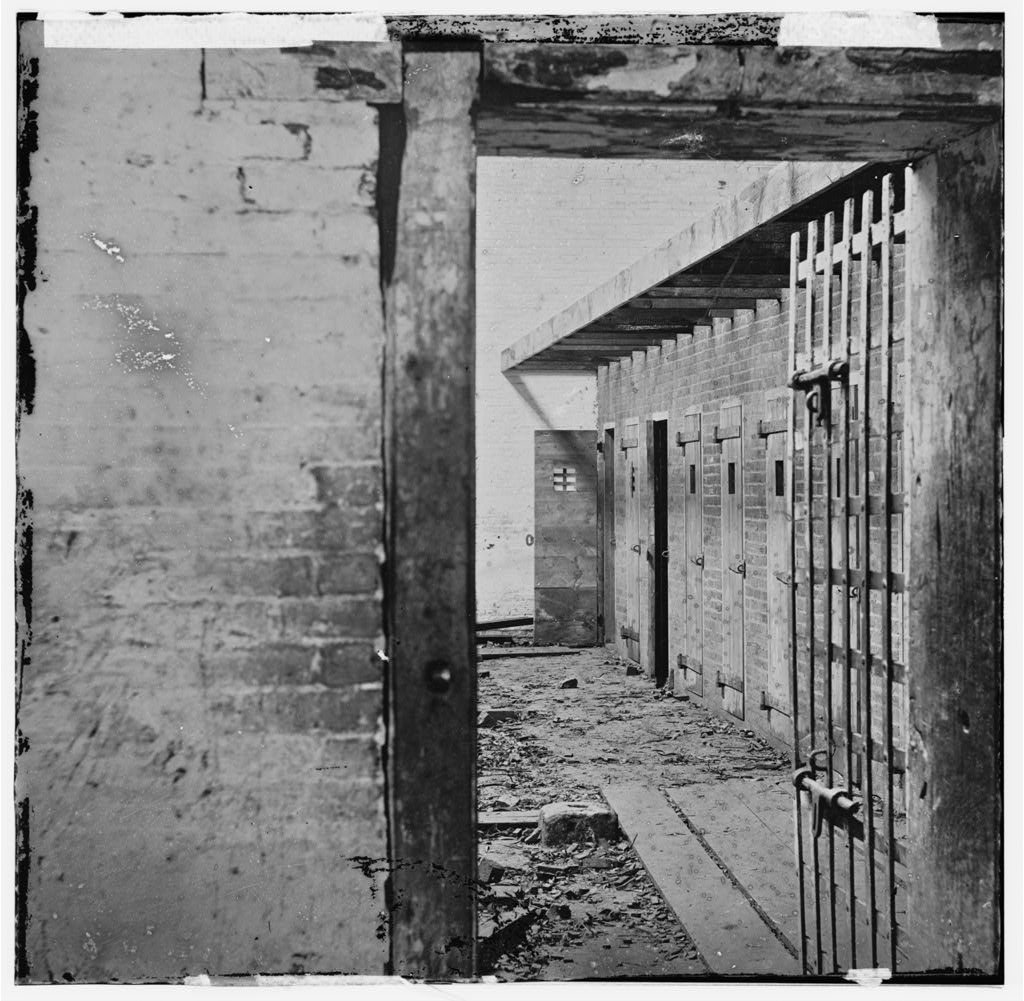

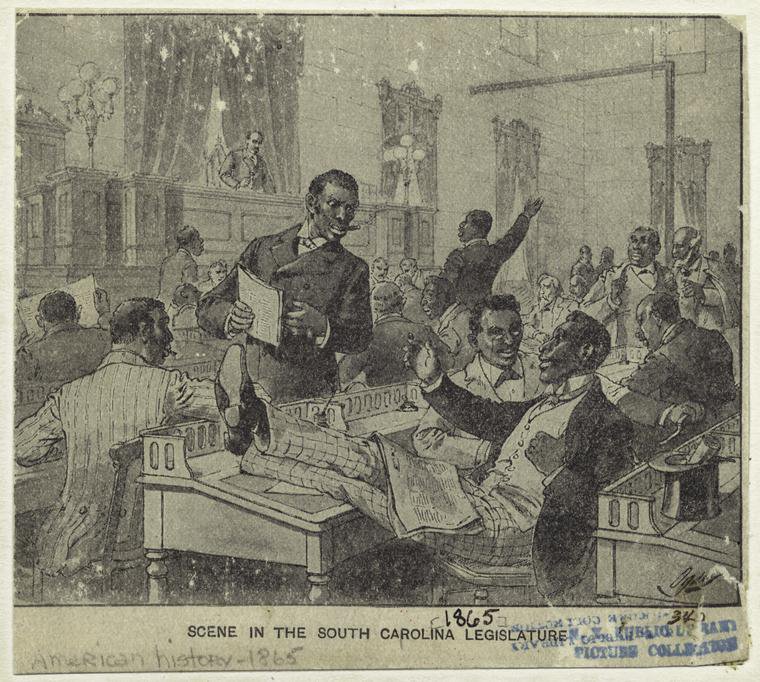

I’d never been interested in writing fiction that involved the U.S., but as the lump refined into individual threads, I changed my mind. They were braiding into a narrative that crossed the Atlantic multiple times, a story of despair, resilience, ambition, and disaster. Characters began to form to carry the narrative, and I started with those who were living their own lives in Liberia before a brutal uprooting and transplantation. Many would end up in Charleston, entry port to more than 40% of Africans who arrived directly from their homeland to the U.S. Many remained in South Carolina for decades, creating the system of rice cultivation that made the state’s plantation owners rich—those from rice-cultivating cultures in Sierra Leone and Liberia in particular fetched higher prices when auctioned because of their agricultural skills. Others would be traded to other states or escape North. In 1822, a group of now-Americans traveled to Liberia to make a new start in Africa, a plan formulated by the American Colonization Society, a white organization whose motives often had racist origins--members felt free persons of color could never assimilate and would “stir up trouble,” so transplanting them to Africa would be preferable to leaving them in place. Despite warnings from the likes of Frederick Douglass, James Forten, David Walker, and William Lloyd Garrison, the movement began to grow. Some slaveholders, such as Mississippi’s Isaac Ross, left deathbed decrees that his slaves should be manumitted on condition they emigrated to Liberia. After the Civil War, voyages continued. About 16,000 relocated in total.

Under the leadership of these Americo-Liberians, Liberia had declared its independence in 1847. Their rule, imposed on indigenes who had not supported the loss of land and power, remained firmly in place until a 1980 coup caused many to flee to the U.S. The succeeding civil war, which saw Charles Taylor’s rise to power, sent many more across the seas, including those without American histories. Firestone’s role in the civil war and the fate of those who are now Americans are only small parts of a complex narrative. By considering the continued lineages of three families, the human element remains key. Many characters are based on real people with surprising stories, while others are fictionalized but probable. I hope you’ll like it! It requires additional research since much is not familiar ground, but how useful that my recent South Porch Artist’s Residency was near Charleston!