CHRONICLE OF THE PALMS

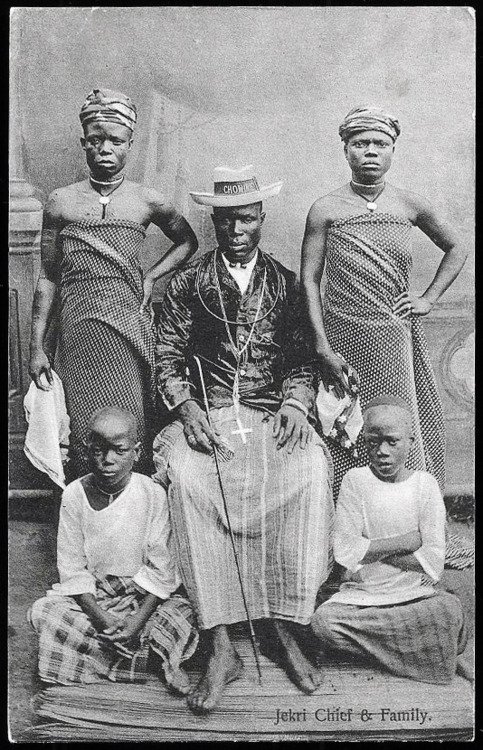

Chronicle of the Palm vol. I: Inverted Worlds follows Antonio Martins d’Abreu, born of an East African mother and a Portuguese father in the late 16th century on the island of Mocambique. Sent to the Jesuit college in Goa, India for his education, he is delighted to be chosen to accompany an elderly priest back to Portugal after completing school. On their voyage to Lisbon, the priest insists on a detour to the West African kingdom of Iwere, whose Catholic monarch has been begging for a cleric to perform baptisms and marriages while he awaits a more permanent arrangement. Soon after their arrival, the priest becomes feverish and dies. Antonio is stranded in a land where his education seems useless—he doesn’t speak the language, know the customs, or have any means of livelihood. The king appoints him as tutor to some of the princes and sons of high-ranking chiefs, and he begins to adjust to his new life, albeit unwillingly. Having carved a position for himself, he is again jolted by a new direction in the monarch’s plans.

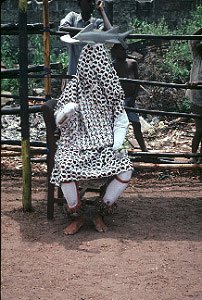

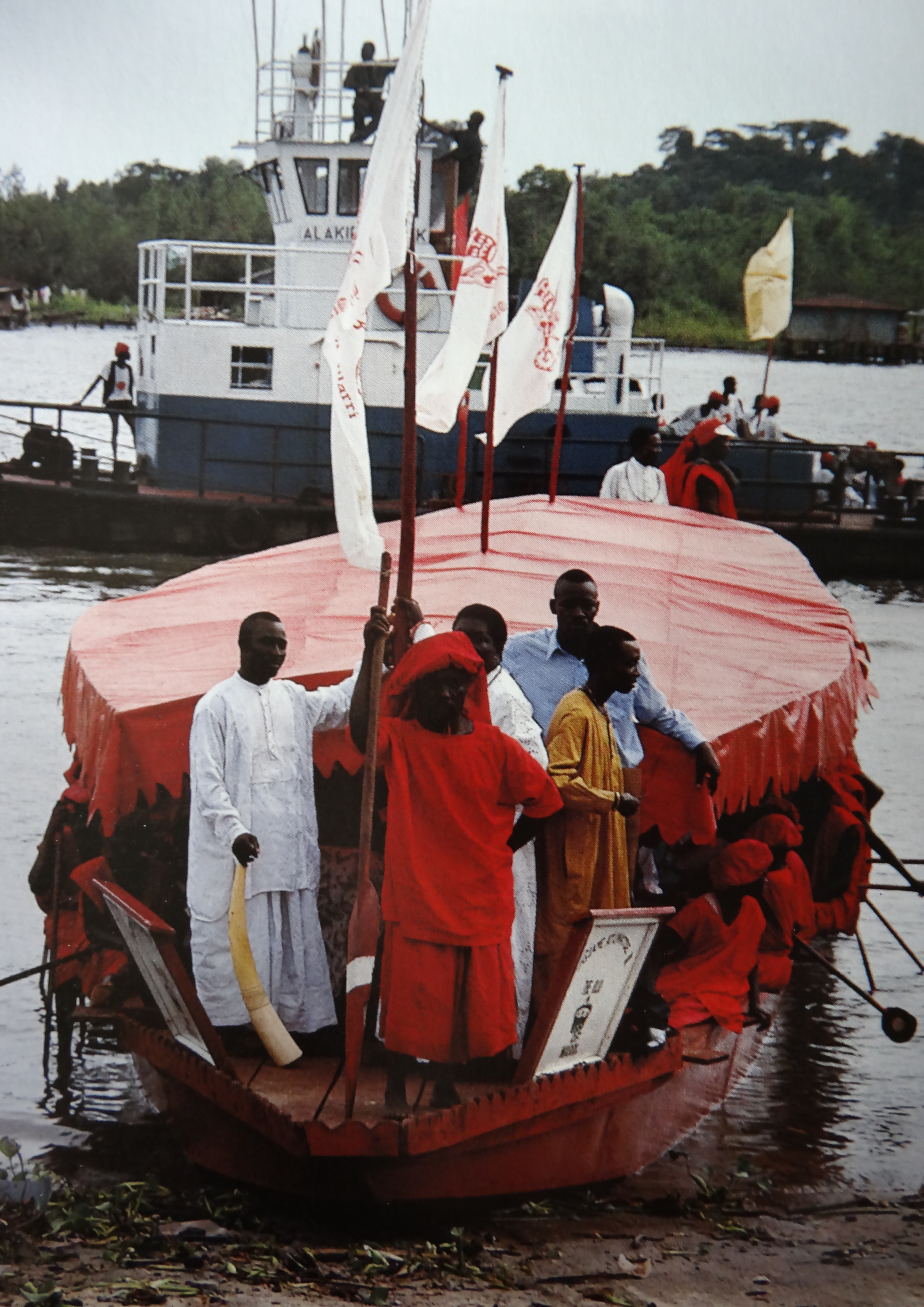

This story, based on historical events surrounding the real monarch and his son, melds fact and fiction in a tale that is part coming-of-age, part fish-out-of-water, and all based on a very real culture unfamiliar to many readers. A short excerpt below provides a taste of its mix of humor, self-pity, and industriousness. The photos give a sense of place, for the author spent significant time there, albeit some centuries later. This volume is complete, and volume 2, begun at the Buinho residency, is underway. A sneak peek may be found here.

I held the world in my hands. Verdade, it was not yet the world, but the roundest calabash gourd Chief Otsodi’s men could find—a little flattened on the end where its stem had joined the vine, but passable. The globe at the colégio had been somewhat larger, a wooden sphere whose engraved paper surface had been inked with many colors, its oceans bearing simpering mermaids and unlikely sea monsters. I had had to find another way. My (well, the padre’s) paper supply was too precious to cut in an attempt to fit it onto a slightly squashed gourd. I had practiced on smaller examples, and found if I used a sandpaper leaf on the surface, the golden hard surface would vanish, replaced by a pithier, more absorbent finish. A heated nail could then produce a satisfyingly dark line to mark the continents. This was a trick I had observed in the market, where the many plain calabashes halved for cups, bowls, and ladles occasionally were relieved by decorated examples from some distant place with burns and scrapings providing designs. Amongst my papers I had a mappamundi I had copied from Ortelius’s atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Tarrarum, shelved in the colégio’s library. Padre Aliandro had been highly impressed. I was less certain how he would have felt about the inked oranges discarded nearby—for transferring flat map to sphere was no easy task for the novice, and I had required practice before essaying the final globe. If my students were to understand the world and its wonders, they would need to see where their tiny kingdom lay.

My schoolroom would open in another day, and I was determined to have my globe ready. If I were to teach them geografia, it was needed. And Homer, Camões, all their tales would have more meaning if the boys could see the places they wrote about. I was sketching the continents with light charcoal to ready their contours for burning, and Agbamu was searching the market for the blue dye used on heavy cotton wrappers so I could color the sea. I had abandoned plans to have some ironmonger create a spinning framework, choosing a less ambitious but infinitely easier approach. When complete, I would place the globe on a simple raffia carrying pad like those girls used on their heads when they fetched water in round-bottomed pots. It could thus be tipped in every direction to reveal the continents as needed. If it lacked the axial tilt of the globes I knew, I could still demonstrate and describe that obliquity, a discovery Tycho Brahe was unfairly credited with—for it was Ulugh Beg, ruler of Samarkand and astronomer extraordinary, who had determined that from his fantastical observatory. Such are the virtues of Jesuíta studies in the East—Eastern inventions are not completely crowded out by those of Europe.

As usual, there was an interruption. Vasco had bounced in with an invitation to see some sharks netted by fishermen, and I was pleased to follow him to the waterside. I was surprised no crowd had gathered, and said so.

“O senhor, every Iwere man has seen all manner of sea creatures—no one is staggered by them.”